The parliamentary hearing of Stellantis chairman John Elkann on March 19 failed to dispel doubts surrounding the future of the Italian automotive industry. Between fanciful interpretations of statistical data and debatable claims about Italy’s strategic relevance, no real clarification was given regarding the Group’s industrial plans for production and employment in Italy

Syntactic Acrobatics – that’s the kind of verbal sleight of hand Stellantis CEO and chairman pro tempore, John Elkann, employed during his appearance before the Italian Parliament on March 19. The hearing, repeatedly requested by the political class, was supposed to shed light on the strategies the Franco-Italian group intends to pursue in the short and medium term in Italy, especially in light of the particularly complex historical moment facing the European automotive sector. But clear answers were nowhere to be found. Instead, Elkann presented a questionable narrative emphasizing the strategic value of Fiat’s, and now Stellantis’s, Italian DNA as a lifeline for the national automotive industry.

This almost felt like a communications prank, coming just months after tensions with the Italian government over the Group’s decision to name the Polish-built Alfa Romeo crossover “Milano” – a move blocked for being misleadingly national – and to remove the Italian tricolor from the Moroccan-assembled Fiat “Topolino” microcars. In short, a short circuit between rhetoric and reality – which took on a borderline farcical tone when Elkann proudly claimed that the Group had always defended employment in Italy, pointing out that while the domestic market had shrunk by 30% over the past 20 years, employment had only fallen by 20%.

According to this rather creative statistical interpretation by the Stellantis chairman, this would mean the Group has protected Italian factory jobs and production despite the sector’s difficulties – even citing €14 billion in taxes paid to the Italian government over the same time frame. However, a recent analysis by Italia Oggi, a financial daily, points out that between early 2021 and the end of 2023, Stellantis’s workforce in Italy dropped by 20%, from 52,740 to 42,700 employees.

The doubts surrounding the future of the Italian automotive industry

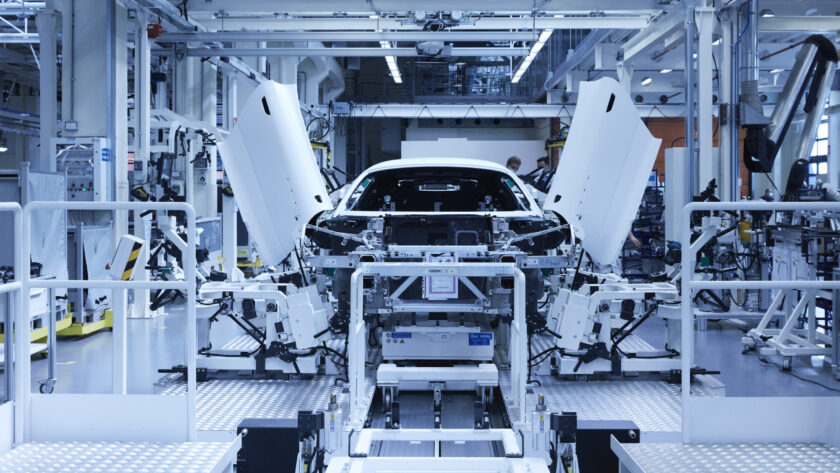

This contraction preceded the Group’s annus horribilis in Italy: 2024, a year in which Stellantis produced just over 283,000 cars at Italian plants – a 45% drop compared to 2023. Including the 192,000 light commercial vehicles built in Italy, the total domestic output barely surpassed 475,000 units. This occurred despite the Italian car market shrinking by only half a percentage point, a downturn hardly sufficient to justify the near-halving of Stellantis’s national factory activity, which triggered furloughs for roughly 20,000 workers.

Prospects for the immediate future are equally bleak. Elkann indicated that 2025 is expected to be another tough year, with only the first signs of recovery anticipated in early 2026 – though by then, the production and commercial structure of Stellantis remains entirely uncertain.

Crucially, Elkann failed to clarify the two most critical issues concerning Stellantis’s future in Italy. The long-promised Gigafactory in Termoli is now indefinitely on hold, and Maserati’s future is tied solely to its Modena plant following the 2023 closure of the Grugliasco facility, which had significantly contributed to the brand’s revival, producing over 40,000 cars in 2017. Last year, production dropped to just 2,250 units, limited to only three models, with workers frequently furloughed and encouraged to transfer to Serbia to support production of the new Fiat “Grande Panda.”

This marks the lowest point in the Trident’s 110-year history, with the very real threat of losing another pillar of Italian automotive excellence — much like what already happened with Lancia, once the vehicle of choice for Italian Presidents and now reduced to under 4,000 units sold annually (with only the aging Ypsilon in the lineup), and with Alfa Romeo, whose once-envied sporting DNA has faded.

Before Stellantis executes its third high-profile “automotive homicide,” a rapid return of Maserati to Ferrari’s direct control, as was the case between 1997 and 2005, might just be the only viable path forward.